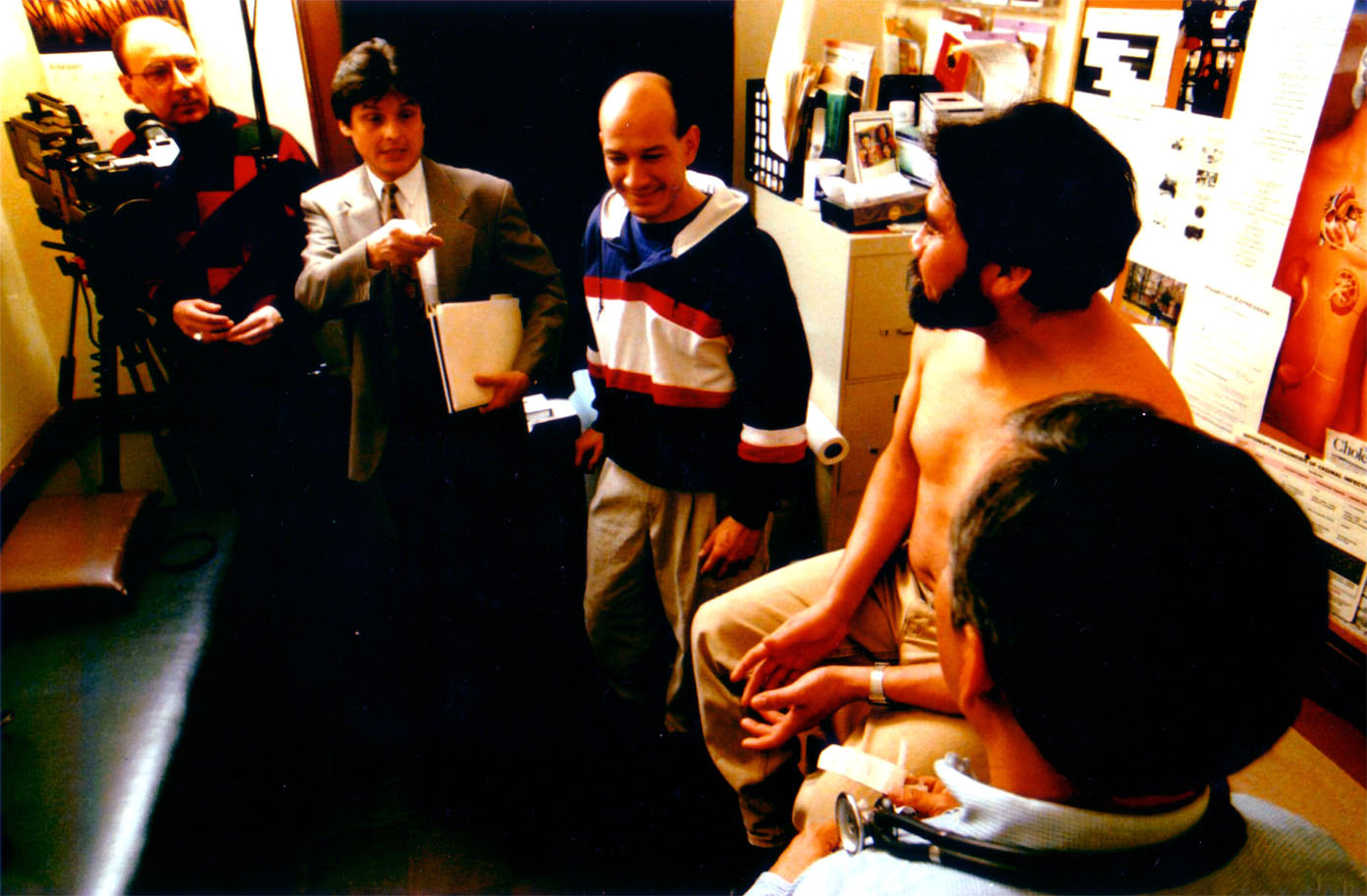

Eduardo López, producer, Arturo Salcedo, host, and Jesús Hidalgo, production assistant, plan a scene for Línea Directa with Lorenzo Cardoso and Dr. Juan Romagoza, director of Clínica del Pueblo (1998).

By Pamela Constable

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, March 12, 1998

On a recent weekday afternoon, in the crowded waiting room of La Clinica Del Pueblo, a man with a clipboard was frantically trying to find a patient. Any patient would do, he explained, as long as she was a mother with a small child.

With a winning smile and an offer of $50, Arturo Salcedo finally persuaded a shy Salvadoran immigrant to bring her son to one of the clinic’s examining rooms. There, Juan Romagoza, director of this “people’s clinic” for low-income Latinos in Columbia Heights, stood ready with a stethoscope.

Then, with a camera whirring, Romagoza pretended to check the boy’s heart and lungs, repeating the staged examination a dozen times until the cameraman declared the scene perfect.

At 6 p.m. Sunday, the mock exam will appear as a 30-second scene in “Linea Directa,” a half-hour public service show on Univision’s Channel 48, which is seen each week by nearly 100,000 Spanish-speaking viewers throughout the Washington area.

“It’s often crazy like this. . . . We have so little time to shoot,” said Salcedo, 38, the host and executive director of the show, which hires members of the community as actors whenever possible “to make it seem more real to people.”

“Linea Directa,” now in its eighth year, is a nonprofit, shoestring operation, based at St. Paul’s College in Northeast Washington. Salcedo’s business partner, Eduardo Lopez, functions as cameraman, director and editor.

This spring, with the help of several foundation grants, they are putting together a series that will examine health issues such as tuberculosis, nutrition, cancer prevention, drug abuse and the lack of health insurance among Latinos.

The clinic’s Romagoza, who is helping to develop the series, said many of his Latino patients lack basic information on health care and don’t follow through with prescribed treatments. For example, he said, a person may come in for a tuberculosis test but then fail to return several days later for the results — or stop taking the medicine too soon, making the tuberculosis strain stronger and more resistant.

“When people see me talking on `Linea Directa,’ they pay more attention. It’s a magic vehicle to wake up their interest and sense of responsibility,” Romagoza said. “In this community, where so few people have money and medical insurance, we don’t have enough resources for cures, but we do have enough for prevention.”

Television shows that present modern medical information in Spanish are needed, Romagoza said, to offset the many ads on Spanish-language television stations featuring psychics and healers who promise to cure everything from from baldness to depression — for a fee.

For Salcedo and Lopez, who have cobbled together at least 200 videotaped programs since 1990, including shows on gang violence and immigration laws, the key is to relate directly to Latino viewers, without histrionics. If the staged presentations or hastily written scripts lack pizazz, at least the information is getting out to people who often have few other sources.

“Every show [in the series] will push the same message: the importance of preventive health care,” said Lopez, 40. “People don’t find out they have hypertension or TB until they end up in the emergency room, with no insurance and no way to pay for treatment, when their condition could have been detected with primary care.”

After several hours of shooting at the clinic, where toddlers nearly upended the light stands, the “Linea Directa” crew moved to an apartment in Petworth, where another obliging patient had agreed to let them shoot a scene in his living room.

This time, the Salvadoran mother, Blanca Majano, 34, was instructed to comfort her sick “husband” — another recruited patient named Lorenzo Cardoso — as he sat in a chair. She blushed as Lopez suggested that she give him a kiss.

Lopez then rummaged through the kitchen, found a leftover pot of beans and asked Majano to serve Cardoso, 40, who was told to look sick and refuse to eat. There was no dialogue to memorize: the scenes would be used with Salcedo’s voice-over explaining the symptoms of tuberculosis.

“People love to volunteer, and it helps that we can pay something, but they are always amazed that so many hours of shooting can end up as a few minutes on tape,” Lopez said as he sprinkled water on Cardoso’s forehead so it would look like he was sweating — and made him swallow Tic-Tac after Tic-Tac to look as if he was taking medicine.

With shooting completed, and the borrowed apartment now strewn with rearranged furniture and filming equipment, Majano rushed off to fetch her other children at school. Salcedo, however, was still on the phone in the kitchen, lining up “patients” for the next day’s scenes.