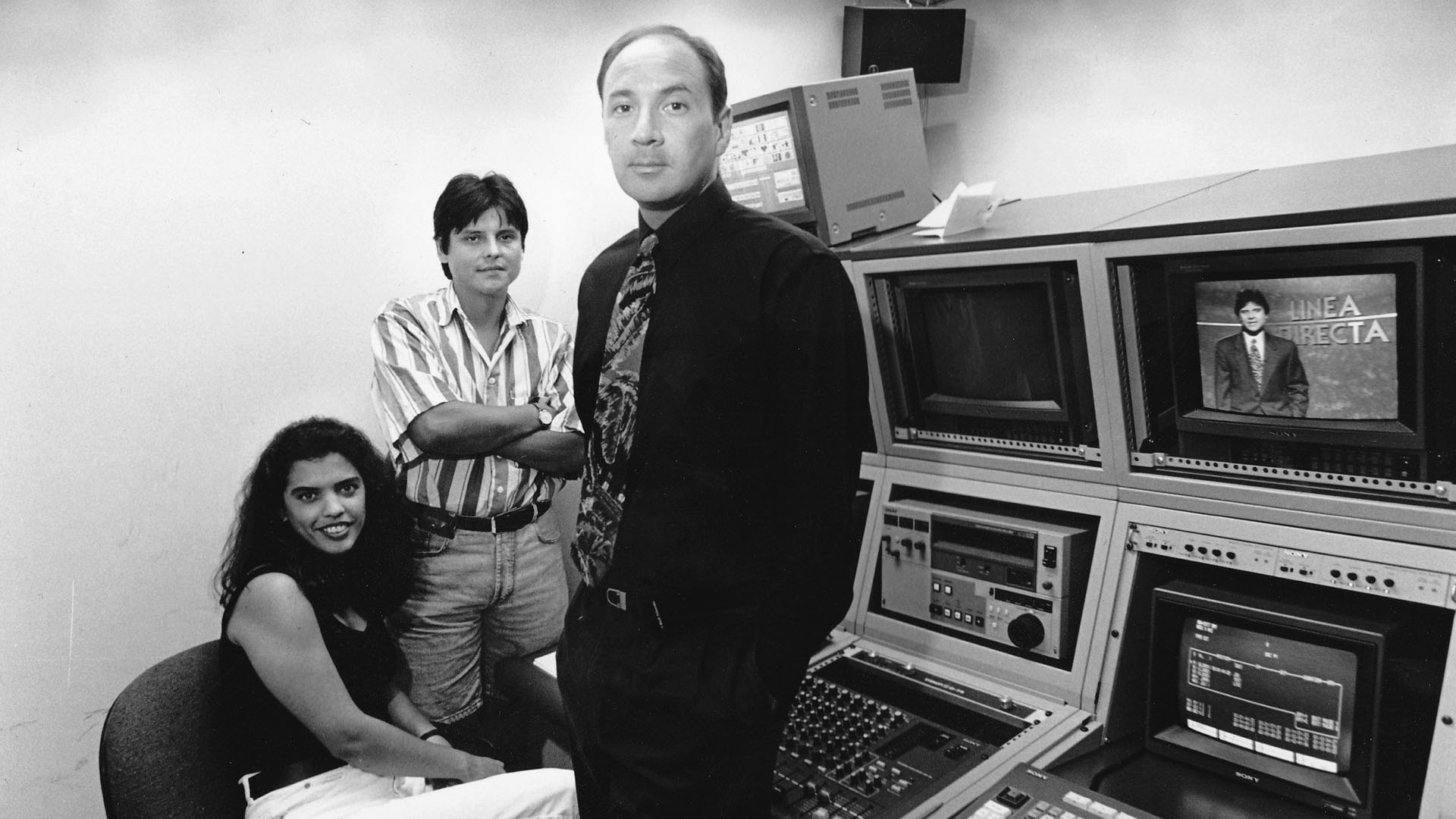

Lorena Sabogal, production assistant, Arturo Salcedo, host, and Eduardo López, producer, at the studio where they produce the public service television series, Línea Directa (1995).

By Pamela Constable

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, August 24, 1995

The video clip shows a Latina riding in a car through Mount Pleasant, with her small daughter perched happily on her lap. Suddenly, the scene shifts to another front seat, where the dummies of a woman and a little girl are hurled into the windshield of a crash-test car at 30 miles an hour.

The message could not be more graphic, but it is one many Latino immigrants in the area have never seen or heard explained in Spanish until now. To make sure the lesson sinks in, the next scene is an interview with a middle-age Salvadoran man named Mario Rivera, his face recognizable to all his Mount Pleasant neighbors.

“I never liked wearing a seat belt, because it was uncomfortable. I only started using one after a policeman stopped me and fined me $75, and now I thank God he did,” the man says in Spanish, describing a recent accident in which his car was smashed but he emerged unhurt. “If it wasn’t for that policeman, I might be dead.”

Eight months after losing its District government funds and disappearing from view, “Linea Directa” — the only Spanish-language public service television show in the Washington area — has fought its way back onto the air. The return premier, which was shown Saturday night on Channel 48 (Univision), focuses on traffic safety; similar half-hour segments will appear at 6 p.m. Saturdays.

The struggle to save “Linea Directa” has been grueling for its longtime co-producers, Eduardo Lopez and Arturo Salcedo. For five years, they operated out of the D.C. Mayor’s Office on Latino Affairs, producing 50 low-budget but popular shows on topics ranging from AIDS prevention to fraudulent psychics. Local Latinos acted in dramatizations, presented testimony and asked audience questions.

Then last winter, both men lost their jobs to the city’s budget cuts, and their program was canceled. But Lopez and Salcedo, determined to save the show, formed a nonprofit corporation and started banging on doors for support.

“It was very hard, but people would recognize me in the street and tell me not to give up,” said Salcedo, 36, who is the program’s host. “One woman came up and said her husband had been a terrible drunk until he saw our show on alcoholism. She said he was scared to death by the part we filmed in prison and he started to change. She gave me $2 and said, Please, you have to keep going.’ ”

Gradually, the team pulled together a patchwork support system, including an agreement with the Office on Latino Affairs to provide a $1,500 monthly contribution and official sponsorship, a low-rent studio at St. Paul’s College in Northeast Washington and pledges of production funds by several foundations and agencies. Each show can cost as much as $30,000 to make.

So far, the money has not stretched far enough to pay either man a regular salary. Lopez is living largely on his severance pay from the city; Salcedo is glad his wife works. Previously, the OLA funded both men’s salaries — a total of about $80,000 — and they raised outside production funds.

For the last month, Lopez and Salcedo frantically have been preparing the auto safety feature: finding accident victims, shooting street scenes, taping voice-overs in a broom closet and editing tape on a console that barely fits in their cramped studio. Last Thursday, they edited until dawn to meet their first deadline.

“There’s a serious problem in the Latino community, especially with men, who say it’s too hot and uncomfortable to wear seat belts or who think it’s macho to put their kid on their lap and teach him to drive,” said Lopez, 37. “That’s why we put real people on the show, to tell their stories and have more of an impact.”

Local nonprofit agencies have strongly supported “Linea Directa’s” return. The auto safety program was paid for with a grant from Mary’s Center for Infant and Maternal Care in Adams-Morgan, which obtained the money through a national auto safety foundation.

There is a more ambitious plan for a fall series on preventing heart disease, funded by the National Institutes of Health. And, if sponsors can be found, the team wants to produce programs on teenage drug abuse, street gangs, changes in immigration law and rights of Latina women.

Lopez and Salcedo plan to continue their successful focus-group format, in which local Latinos are consulted in advance so the programs reflect community concerns and level of knowledge, rather than relying on specialists.

“Linea Directa” was one of the most effective programs I’ve ever seen, and its return is a great joy to us,” said Juan Romagoza, director of the Clinica del Pueblo in Mount Pleasant. “It informed the community in an accessible way. It generated debate about serious problems, and it touched people’s hearts.”